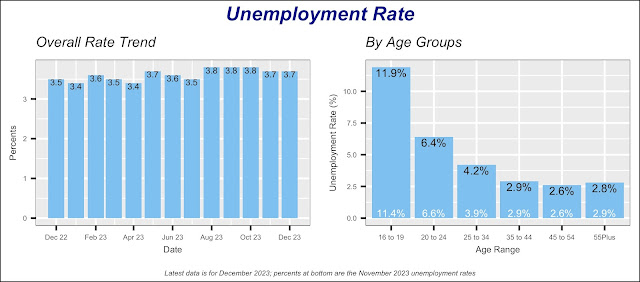

Total employment in the U.S. has recovered nicely over the last four years, since the pandemic shutdown back in 2020. But, as is always the case, not all the states have enjoyed a similar experience. Before reviewing the states' employment performance let's take a look at the overall U.S. employment situation.

U.S. total employment stood at 158.1 million jobs in March of this year, almost 6.5 million jobs above the pre-pandemic level of 152.0 million. Employment shrunk by 21.6 million jobs between February and May 2020, the result of the government's draconian reaction to the pandemic. But two years later, by June 2022, employment reached 152.3 million jobs, slightly higher than the pre-pandemic high reached in February 2020. This is illustrated in the chart below.

Employment growth over the last four years can be split into two periods. The first one is from April 2020 to June 2022, when employment rose from 130.4 million to 152.3 million. The 21.6 million increase in the number of jobs brought the total employment level to what it was right before the pandemic. That is, the 21.6 million jobs were not "new" jobs, but rather "recovered" jobs from the pandemic collapse.

The second period is from June 2022 to March 2024, when the number of jobs rose from 152.3 million to their current level. That is a 6.49 million (3.8%) gain, truly new jobs.

Furthermore, a majority of the recent new jobs are not full-time. Nearly six of ten new jobs (58%) created in the last year were part-time. Also, unlike prior history when the number of part-time jobs fell during economic expansions, we have seen them increasing in the current recovery.

All the states are not equal

Despite the recovery and strength of national employment, we find different responses at the state level. That is, there are several states which are still lagging in their employment recovery. At the same time there are many which already exceed their pre-pandemic levels.

The chart below displays fifteen states with employment below their pre-pandemic peak. Their current employment is still lower than that as of February 2020, or earlier.

Leading with the biggest gap is North Dakota where latest employment of nearly 440 thousand is 6.2% below its maximum level, reached back in 2014 at the height of the state's fracking boom. Also this state's latest employment is lower than its level in February 2020.The next state is Washington DC (considered a state for most geographical analysis) with employment still 4.4% below its pre-pandemic level. DC is followed by Hawaii lagging 3.9% behind its employment in February 2020. Both of these two states are characterized by high employment concentration in one sector.

Nearly twenty percent of the jobs in Hawaii originate from the Leisure & Hospitality sectors which, as we know, have been hit the hardest since the pandemic.

Employment in DC is heavily concentrated in the Government sector and the city has had a persistently high unemployment rate. At least for the last two decades, the unemployment rate in DC has exceeded the national rate by more than one percent.

West Virginia and Wyoming lag their previous employment peak by similar amounts. Current employment in West Virginia is 2.8% lower than its peak employment back in 2013, and Wyoming is 2.7% below the maximum employment it had reached back around 2009, in the middle of the Great Recession.

Employment in Louisiana is still 2.5% lower than in February 2020. Further, employment recovery in the state has stalled over the last twelve months.

Connecticut is an unusual place. The latest employment actually exceeds its level right before the pandemic, by a minimal amount (just 8,400 jobs out of 1.7 million). But the state's employment has never recovered to its level before the 2008-2009 recession, more than fifteen years ago.